The Critical Role of Instrumentation in Industrial Safety: A Comprehensive Guide

Modern industrial landscapes, from vast petrochemical complexes and power generation plants to intricate manufacturing facilities, are inherently complex environments where even minor malfunctions can escalate into catastrophic events. The safety of personnel, the integrity of equipment, the protection of the environment, and the continuity of operations hinge on robust safety measures. At the forefront of these defenses are advanced instrumentation systems, meticulously designed not just to monitor processes but to actively prevent and mitigate hazardous situations.

This comprehensive guide delves deep into the foundational concepts and cutting-edge technologies that underpin safety instrumentation, providing an educational and training-oriented perspective. We will explore the architecture and lifecycle of Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS), understand how Safety Integrity Levels (SIL) are determined to quantify risk reduction, and navigate the complexities of Hazardous Area Classification alongside the critical principles of Intrinsic Safety. By understanding these pillars, professionals can better appreciate the intricate dance between technology and human vigilance that ensures industrial safety.

1. Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS): The Last Line of Automated Defense

Safety Instrumented Systems (SIS), often referred to as Emergency Shutdown Systems (ESD) or Process Safety Systems (PSS), represent an independent and dedicated layer of protection in industrial facilities. Their primary purpose is singular: to automatically bring a process to a safe state when predetermined hazardous conditions arise, thereby preventing accidents or mitigating their severity. Unlike basic process control systems (BPCS) which focus on operational efficiency, throughput, and product quality, SIS operates on a “fail-safe” principle, employing specialized, highly reliable hardware and software designed specifically for safety functions.

The independence of the SIS from the BPCS is paramount. This separation ensures that a failure in the basic control system does not simultaneously compromise the safety system. This independence encompasses physical separation, logical separation, and distinct management procedures, preventing common cause failures that could lead to dangerous situations. The design philosophy of SIS dictates that it should only activate when a hazardous condition is imminent or present, acting as the ultimate automated safeguard when other control layers have failed or are insufficient.

Key Components of a Safety Instrumented System

An SIS functions as a complete safety loop, from detection to action. It typically comprises three core elements that work in concert to achieve the required safety function:

1.1. Sensors (Input Elements)

These are the “eyes and ears” of the SIS, responsible for detecting abnormal or hazardous conditions within the process. Their role is to continuously monitor critical process parameters and provide accurate, reliable data to the logic solver.

- Function: To accurately and reliably measure process variables (e.g., pressure, temperature, flow, level) or detect the presence of hazardous substances (e.g., flammable gases, toxic gases) that could lead to an unsafe state. The reliability of these inputs is paramount, as incorrect or failed readings can compromise the entire safety function.

- Types and Applications:

- Pressure Transmitters: Crucial for detecting overpressure or underpressure conditions in vessels, pipelines, or reactors, which could lead to rupture, implosion, or loss of containment.

- Temperature Probes/Transmitters: Monitor excessive heating or cooling, vital for processes where exothermic reactions, freezing, or material degradation are risks. Examples include reactors, furnaces, and cryogenic systems.

- Flow Meters: Detect abnormal flow rates that could indicate leaks, blockages, pump failures, or runaway reactions, ensuring proper material balance and preventing overflows or dry-run conditions.

- Level Transmitters: Monitor liquid levels to prevent overfilling of tanks (leading to spills) or running dry of vessels (leading to overheating or process damage).

- Gas Detectors: Essential for detecting the presence of flammable or toxic gases in the atmosphere, triggering alarms and shutdown sequences before concentrations reach dangerous levels. These are often strategically placed in areas prone to leaks.

- Flame Detectors: Identify the presence of fire, typically in high-risk areas like pump alleys, storage tank farms, or loading racks, initiating fire suppression or isolation actions.

- Reliability and Redundancy: Sensors used in SIS must meet stringent reliability standards. To enhance availability and prevent spurious trips (unnecessary shutdowns) or, more critically, failure to trip when required (dangerous failures), redundant configurations are often employed. Common architectures include:

- 1-out-of-1 (1oo1): Single sensor. Least reliable, only used for very low SILs or where consequences are minor.

- 1-out-of-2 (1oo2): Two sensors, if one fails, the system trips. High availability (prevents dangerous failures) but prone to spurious trips.

- 2-out-of-2 (2oo2): Two sensors, both must agree for a trip. Low spurious trip rate but can fail dangerously if one sensor fails undetected.

- 2-out-of-3 (2oo3): Three sensors, two must agree for a trip. Offers high availability and low spurious trip rate (can tolerate one sensor failure without tripping or failing dangerously). This is a common and robust architecture for higher SIL applications.

- Diversity: To mitigate common cause failures (where a single event causes multiple redundant components to fail), diversity in technology (e.g., using a pressure transmitter and a level switch for an overfill protection) or manufacturer can be used.

- Failure Modes: SIS sensors are designed to “fail safe” where possible (e.g., a broken wire or power loss causes a signal that initiates a safe state). However, systematic failures (e.g., incorrect calibration, environmental degradation, design flaws) must also be addressed through rigorous design, installation, testing, and maintenance protocols.

1.2. Logic Solvers (Logic Elements)

The “brain” of the SIS, responsible for processing input signals from sensors and executing predefined safety actions based on programmed logic. These are the decision-making core of the safety function.

- Function: To receive signals from input devices, evaluate them against a pre-programmed safety logic (e.g., “if pressure exceeds X AND temperature exceeds Y for 5 seconds, THEN close valve Z and open vent valve A”), and send precise commands to final elements. The logic is typically based on Boolean algebra (AND, OR, NOT gates) or sequence functions.

- Hardware: Typically specialized Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) known as Safety Instrumented Controllers (SICs) or Safety PLCs. These differ significantly from conventional PLCs used for basic process control:

- Certified for Safety: They are designed, manufactured, and certified to meet the stringent requirements of functional safety standards (IEC 61508), ensuring very low probability of dangerous undetected failures.

- Redundancy: Often feature redundant CPUs, power supplies, and I/O modules (e.g., Triple Modular Redundancy – TMR, Dual Redundant) for extreme fault tolerance. If one component fails, a redundant one takes over without interrupting the safety function.

- Extensive Self-Diagnostics: Incorporate sophisticated internal self-diagnostic capabilities (e.g., watchdog timers, memory checks, input/output signal validation) to detect internal faults and immediately move to a safe state or signal a fault to operators, ensuring continuous monitoring of their own health.

- Hardware Diversity: Some high-integrity systems may use diverse logic solver technologies in parallel to prevent systematic failures related to a specific architecture or software.

- Software: Programmed using specific safety-certified programming languages (often compliant with IEC 61131-3, but with additional safety constraints and specific function blocks for safety applications). The software development process must be meticulously controlled, verified, and validated to prevent programming errors (systematic failures) that could render the SIS ineffective.

- Segregation: The logic solver and its associated wiring are physically and logically segregated from the BPCS. This separation prevents interference and ensures that a malfunction in the basic control system cannot propagate to the safety system. This can involve separate control rooms, separate cabinets, and dedicated communication networks.

1.3. Final Elements (Output Elements)

These are the “muscle” of the SIS, responsible for executing the physical safety actions that bring the process to a safe state. They are the components that directly interact with the process.

- Function: To directly interact with the process to bring it to a safe state. This often involves stopping energy flow, isolating hazardous materials, stopping rotation, or initiating a mitigating action in a rapid and reliable manner.

- Types and Fail-Safe Design:

- Safety Valves:

- Emergency Shut-down (ESD) Valves: Designed to quickly close (fail-closed, FC) to isolate a process section, stop the feed of hazardous materials, or prevent flow from a ruptured line. They are spring-returned or pneumatically actuated to ensure they move to the safe position upon loss of power or air.

- Blowdown Valves (BDV): Rapidly open (fail-open, FO) to vent pressure from vessels or pipelines, preventing overpressure.

- Vent Valves: Used to release pressure or unwanted substances to a flare or safe vent.

- Circuit Breakers/Motor Disconnect Switches: Cut off electrical power to pumps, motors, heaters, or other equipment that could contribute to a hazard if left energized. These are common in electrical safety functions.

- Fire Suppression Systems: Activate deluge systems, foam systems, or inert gas release (e.g., CO2, Nitrogen) to extinguish fires or prevent their spread.

- Pump Shut-off: Stopping pumps to cease fluid transfer or circulation of hazardous materials.

- Safety Valves:

- Criticality: The final elements are arguably the most critical part of the safety loop, as they are the last physical barrier between a hazardous condition and a potential accident. Their response time, reliability, and fail-safe design are paramount. Fast-acting valves are essential where rapid isolation is required.

- Maintenance and Testing: Regular and rigorous testing (known as proof testing, discussed below) and maintenance are crucial to ensure that final elements can perform their intended safety function on demand, even after long periods of inactivity. This includes cycling valves, checking limit switches, and verifying seal integrity.

Example: In a large chemical reactor, if temperature sensors (input) detect that the internal temperature has exceeded the safe operating limit due to a cooling system failure, the Safety Instrumented Controller (logic solver) receives these signals. Based on its programmed logic, it immediately commands the Emergency Shut-down (ESD) valve (final element) on the reactant feed line to close, simultaneously opening a vent valve to depressurize the vessel and activating an emergency cooling system. This sequence prevents a runaway exothermic reaction that could lead to an explosion, demonstrating the complete, automated cycle of an SIS.

Image Suggestion:

SIS Block Diagram

Purpose: Clearly illustrates the fundamental components and their interrelationship in a safety loop, emphasizing the closed-loop nature of SIS.

Diagram showing the components of a Safety Instrumented System (SIS) - Sensors, Logic Solver, and Final Elements interacting with a process.]

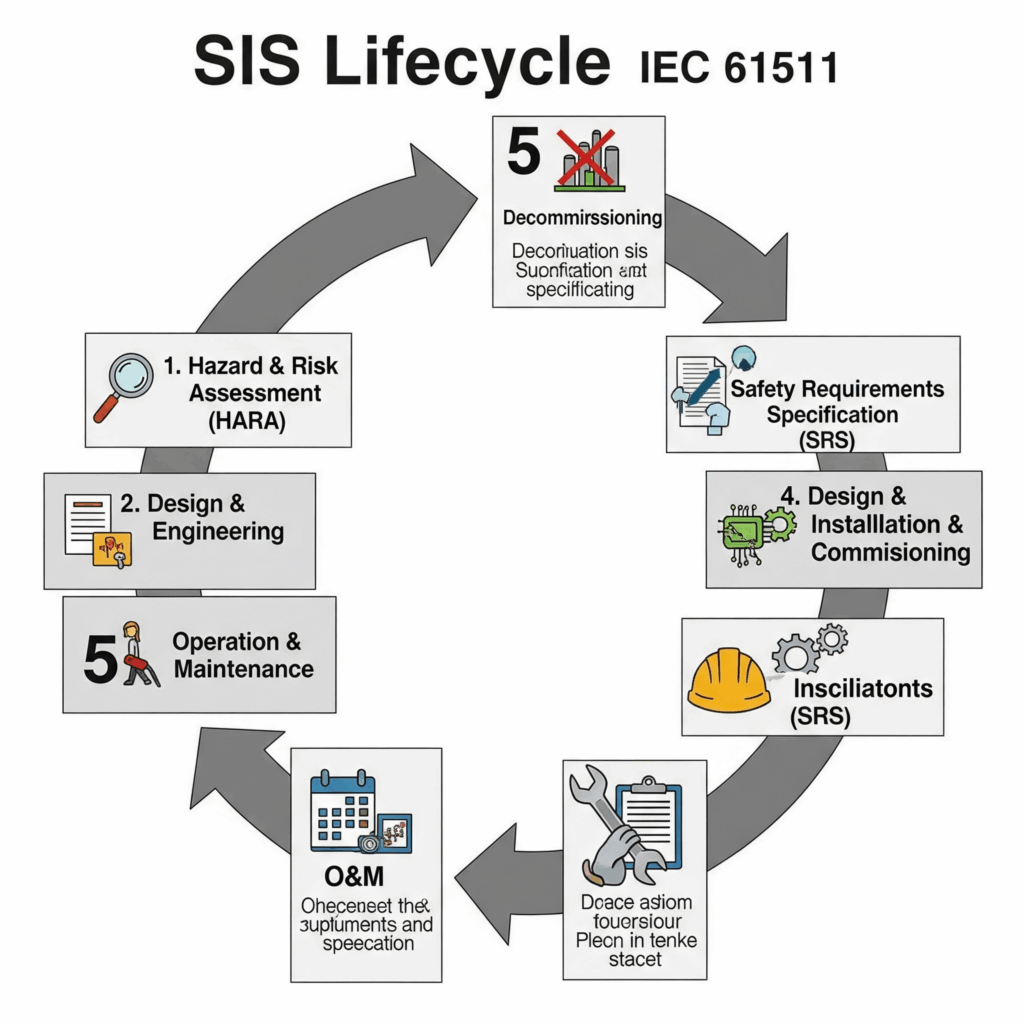

The SIS Design Lifecycle (IEC 61511 Compliance)

The design, implementation, and operation of Safety Instrumented Systems are governed by stringent international standards, primarily IEC 61508 (Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems) and its process industry-specific derivative, IEC 61511 (Functional Safety – Safety Instrumented Systems for the Process Industry Sector). These standards mandate a comprehensive risk-based lifecycle approach to ensure the integrity of the SIS throughout its entire lifespan, from initial concept to decommissioning. This systematic approach is crucial for achieving and maintaining the required Safety Integrity Level (SIL).

1. Hazard and Risk Assessment (HARA)

- Purpose: This is the foundational step for all safety efforts. It involves systematically identifying all potential hazards associated with a process, assessing the risks (likelihood and severity of consequences), and determining if existing safeguards (e.g., basic process control, alarms, human intervention) are sufficient to reduce the risk to a tolerable level.

- Methods: Common techniques used in this phase include:

- Hazard and Operability (HAZOP) Studies: A structured and systematic examination of a complex planned or existing process or operation to identify and evaluate problems that may represent risks to personnel or equipment, or prevent efficient operation.

- Process Hazard Analysis (PHA): A broad term encompassing various methods like “What-If” Analysis, Checklists, Fault Tree Analysis (FTA), and Event Tree Analysis (ETA) to identify potential hazards and their causes/consequences.

- Outcome: The HARA identifies the need for Safety Instrumented Functions (SIFs) where existing safeguards are inadequate. For each identified SIF, a target Safety Integrity Level (SIL) is determined based on the residual risk that needs to be reduced.

2. Safety Requirements Specification (SRS)

- Purpose: Once the HARA identifies the need for SIS and a target SIL, the SRS formally defines the functional and integrity requirements for each Safety Instrumented Function (SIF). This document is absolutely crucial as it forms the basis for the subsequent design, implementation, and verification of the SIS. It acts as the blueprint for the SIS.

- Content: The SRS is a comprehensive document that specifies:

- Functional Requirements: The precise process conditions that will trigger the SIF (e.g., “Pressure in vessel V-101 exceeds 15 barg”).

- Safe State: The exact safe state the process must achieve upon activation (e.g., “Close valve XV-102 and open vent valve HV-103”).

- Required SIL: The target Safety Integrity Level (e.g., SIL 2, SIL 3) for the SIF.

- Response Time: The maximum time allowed for the SIF to bring the process to a safe state after detection of the hazardous condition.

- Alarm Points: The associated alarms and their setpoints.

- Bypass Conditions: Under what conditions, and for how long, the SIF can be bypassed, and what alternative safeguards are required during that time.

- Manual Shutdowns: Requirements for manual initiation of the safety function.

- System Diagnostics: Requirements for self-diagnostics within the SIS.

- Proof Testing Requirements: Frequency and scope of testing to reveal dangerous undetected failures.

- Human-Machine Interface (HMI) Requirements: How operators will interface with the SIS (e.g., indications, acknowledgements).

3. Design and Engineering

- Purpose: Translating the detailed SRS into a tangible SIS architecture, selecting specific components, and ensuring the design achieves the required SIL.

- Activities: This phase is highly technical and involves:

- Architecture Selection: Deciding on the sensor, logic solver, and final element configurations (e.g., 1oo1, 1oo2, 2oo3 voting).

- Component Selection: Choosing specific safety-certified sensors, safety PLCs, and safety valves that meet the SIL requirements and environmental conditions.

- Hardware and Software Design: Developing detailed wiring diagrams, P&IDs (Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams) with SIS elements, control narratives, and programming the safety logic within the SIC.

- SIL Verification (Achieved SIL Calculation): Performing quantitative calculations (using failure rate data for components) to prove that the proposed design’s achieved SIL meets or exceeds the target SIL specified in the SRS. This involves considering hardware fault tolerance, safe failure fraction, diagnostic coverage, and proof test intervals.

- Common Cause Failure (CCF) Analysis: Designing to mitigate CCFs by introducing diversity, segregation, and robust installation practices.

- Documentation: Preparing comprehensive engineering documentation, including loop diagrams, cause-and-effect matrices, and logic solver program details.

4. Installation and Commissioning

- Purpose: Ensuring the SIS is correctly installed, wired, configured, and functions exactly as per the approved design and SRS.

- Activities: This phase is critical for physical integrity and proper functionality:

- Physical Installation: Mounting sensors, logic solvers, and final elements according to design specifications and hazardous area requirements.

- Wiring and Connections: Meticulous wiring, ensuring proper segregation of safety circuits from non-safety circuits, and correct termination.

- Pre-commissioning Checks: Verifying continuity, insulation resistance, and correct power supply.

- Software Loading and Configuration: Uploading the safety logic program to the SIC and configuring all parameters.

- Site Acceptance Testing (SAT) and Functional Acceptance Testing (FAT): Rigorous testing performed on site. This includes testing individual components, then entire safety loops, simulating hazardous conditions to verify that the SIS initiates the correct safety action within the specified response time. Comprehensive documentation of all test results is mandatory.

5. Operation and Maintenance

- Purpose: Maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of the SIS throughout its entire operational life. This is an ongoing commitment to ensure the system remains reliable and continues to perform its safety function on demand.

- Activities: This is a continuous process involving:

- Proof Testing: Regular, pre-planned tests designed to reveal dangerous undetected failures that would prevent the SIS from performing its safety function. The frequency and thoroughness of these tests are directly linked to the achieved SIL. These tests often involve partially or fully actuating the safety loop components (e.g., stroking a safety valve, simulating a high-pressure condition to trigger the trip).

- Bypass Management: Strict procedures for managing temporary bypasses of SIFs (e.g., during maintenance or calibration). Bypasses must be authorized, clearly indicated, time-limited, and require alternative safeguards to be in place (e.g., manual intervention, administrative controls) to cover the period the SIF is compromised.

- Management of Change (MOC): Any modification to the process, equipment, SIS hardware, or SIS software (including parameter changes) must follow a formal MOC procedure. This ensures that the safety integrity of the system is not inadvertently compromised by changes, and that all documentation is updated.

- Competence Management: Ensuring that all personnel involved in the operation, maintenance, testing, and modification of SIS are adequately trained, assessed, and competent. This includes engineers, technicians, and operators.

- Performance Monitoring: Continuously tracking SIS performance, including spurious trip rates, dangerous failure rates, and proof test results, to identify any degradation in performance or emerging issues.

- Preventive Maintenance: Routine checks, calibration, and replacement of components as per manufacturer recommendations or operational experience.

6. Decommissioning

- Purpose: Safely removing the SIS when the process or facility is no longer operational or the safety function is no longer required.

- Activities: Ensuring that the process is brought to a safe and stable state before the SIS is deactivated or removed, and that all hazardous materials are cleared. Proper procedures must be followed to avoid creating new hazards during the shutdown and dismantling.

This rigorous Lifecycle approach ensures that SIS integrity is maintained from conception through to disposal, forming a critical layer in the overall process safety management strategy. It’s a continuous cycle of identification, design, implementation, and verification, underpinning the safety of industrial operations.

SIS Lifecycle Flowchart

Purpose: Visualizes the structured, cyclical, and continuous nature of the SIS management process, highlighting its systematic approach.

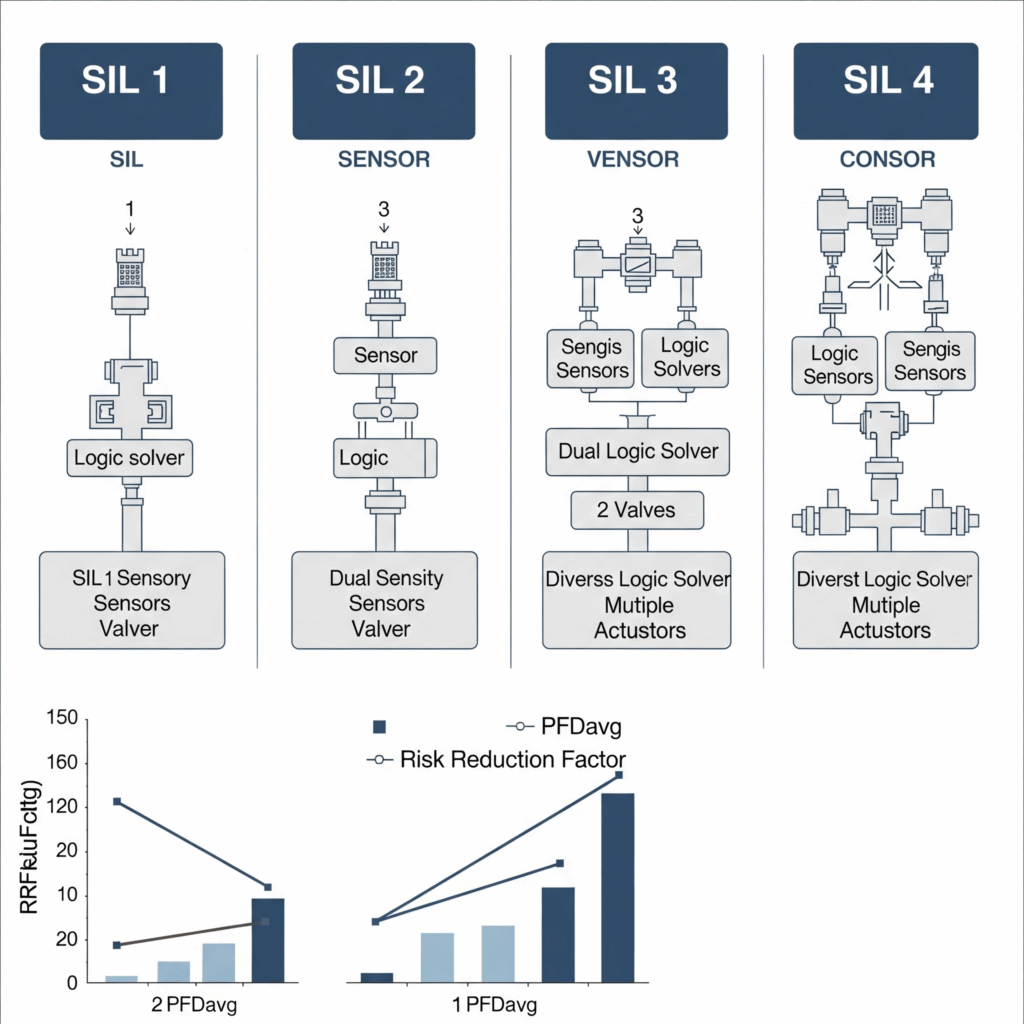

2. SIL (Safety Integrity Level) Determination: Quantifying Risk Reduction

Safety Integrity Level (SIL) is a critical concept in functional safety, providing a quantifiable measure of the reliability performance required for a Safety Instrumented Function (SIF). Defined by international standards IEC 61508 (Functional Safety of Electrical/Electronic/Programmable Electronic Safety-Related Systems) and IEC 61511 (Functional Safety – Safety Instrumented Systems for the Process Industry Sector), SIL ranks from 1 (lowest risk reduction) to 4 (highest risk reduction) based on the probability of a safety function failing to perform its intended action on demand. Essentially, SIL tells us “how good” a safety function needs to be to achieve the necessary risk reduction to bring a specific risk down to a tolerable level.

Understanding PFDavg and RRF

For most process industry applications, SIS operates in a “low demand” mode. This means the safety function is only called upon infrequently (e.g., once a year or less), typically in response to an abnormal event. For such systems, the primary metric for SIL determination and verification is the Probability of Failure on Demand (PFDavg).

- PFDavg (Probability of Failure on Demand average): This represents the average probability that a Safety Instrumented Function (SIF) will fail to perform its specified safety function when called upon to do so. A lower PFDavg value indicates higher reliability and, therefore, a higher SIL. For example, a PFDavg of 10−3 means there is a 1 in 1,000 chance that the SIF will fail when it is needed.

- RRF (Risk Reduction Factor): This is the inverse of PFDavg (RRF=PFDavg1). It quantifies how many times the risk is reduced by the implementation of the SIF. For example, an RRF of 1,000 means the SIF is expected to reduce the frequency of the hazardous event by a factor of 1,000. This is a more intuitive way for some to grasp the impact of the safety function.

The relationship between SIL, PFDavg, RRF, and the corresponding availability is crucial for understanding the performance requirements of an SIS:

| SIL Level | PFDavg Range (Low Demand) | RRF Range (Low Demand) | Required Availability | Implications for Design & Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIL 1 | 10−1 to 10−2 | 10 to 100 | 90% – 99% | Achieved with single, well-chosen components (e.g., 1oo1 sensor/valve). Lowest complexity. |

| SIL 2 | 10−2 to 10−3 | 100 to 1,000 | 99% – 99.9% | Requires higher quality components, often some redundancy (e.g., 1oo2D logic, 1oo2 valve voting). Moderate complexity. |

| SIL 3 | 10−3 to 10−4 | 1,000 to 10,000 | 99.9% – 99.99% | Significant redundancy (e.g., 2oo3 logic, 2oo3 valve voting), high diagnostic coverage, rigorous testing. High complexity and cost. |

| SIL 4 | 10−4 to 10−5 | 10,000 to 100,000 | 99.99% – 99.999% | Extremely high redundancy and diversity, very stringent design, operation, and maintenance. Extremely rare in process industries due to prohibitive cost and complexity. |

Note: While SIL 4 exists in the standards, it is rarely achieved or required in the process industry due to the extreme costs, complexity, and often unmanageable proof testing requirements involved. Most process safety applications fall within SIL 1, 2, or 3.

Methods for SIL Determination

Several structured methods are employed to determine the appropriate SIL for each Safety Instrumented Function. These methods range from qualitative to semi-quantitative, each offering different levels of rigor and precision. The choice of method often depends on the complexity of the process, the severity of the consequences, and company policy.

2.1. Risk Matrix

- Description: A qualitative tool that visually represents the relationship between the likelihood (or frequency) of an event and the severity of its potential consequences. It’s a foundational tool in hazard assessment.

- How it works: A grid is constructed with ‘Likelihood’ on one axis (e.g., ‘Rare’, ‘Unlikely’, ‘Possible’, ‘Likely’, ‘Frequent’, or frequency ranges like >1/year, <1/10yr) and ‘Severity’ on the other (e.g., ‘Minor Injury’, ‘Major Injury’, ‘Fatality’, ‘Multiple Fatalities’, ‘Catastrophe’). Each cell in the matrix corresponds to a specific risk level (e.g., ‘Low’, ‘Medium’, ‘High’, ‘Intolerable’), and often, a corresponding target SIL. For example, a ‘High’ risk cell might directly indicate a need for SIL 2 or 3.

- Application: Primarily used for initial screening during the Hazard and Risk Assessment (HARA) phase. It provides a quick, high-level indication of required SILs. Its simplicity is an advantage, but it relies heavily on expert judgment and can lack the precision needed for complex systems. Different companies may have customized risk matrices tailored to their specific operations and risk tolerance.

2.2. Risk Graph

- Description: A semi-quantitative, step-by-step decision-making tool that guides the user through a series of nodes representing different risk parameters. It’s a more structured approach than a simple risk matrix.

- How it works: The graph typically starts by evaluating the potential Consequence (C) of the hazardous event (e.g., C1: minor injury, C2: serious injury, C3: single fatality, C4: multiple fatalities, catastrophe). Depending on the consequence, the path leads to evaluating the Exposure (E) of personnel to the hazard (e.g., E1: rare to frequent exposure, E4: continuous presence in the hazard zone). Then, the possibility of Avoidance (A) by personnel or other safeguards (e.g., A1: usually possible, A3: rarely possible). Finally, the Probability (P) of the unwanted event occurring without the SIF (e.g., P1: very low, P3: relatively high). Each path through the graph, based on the selected parameters, leads to a recommended SIL.

- Application: Provides a more structured and transparent approach than a simple risk matrix, allowing for a more nuanced assessment by considering multiple risk parameters. It’s often used in the early stages of a project or for less complex systems where a full LOPA might be overkill.

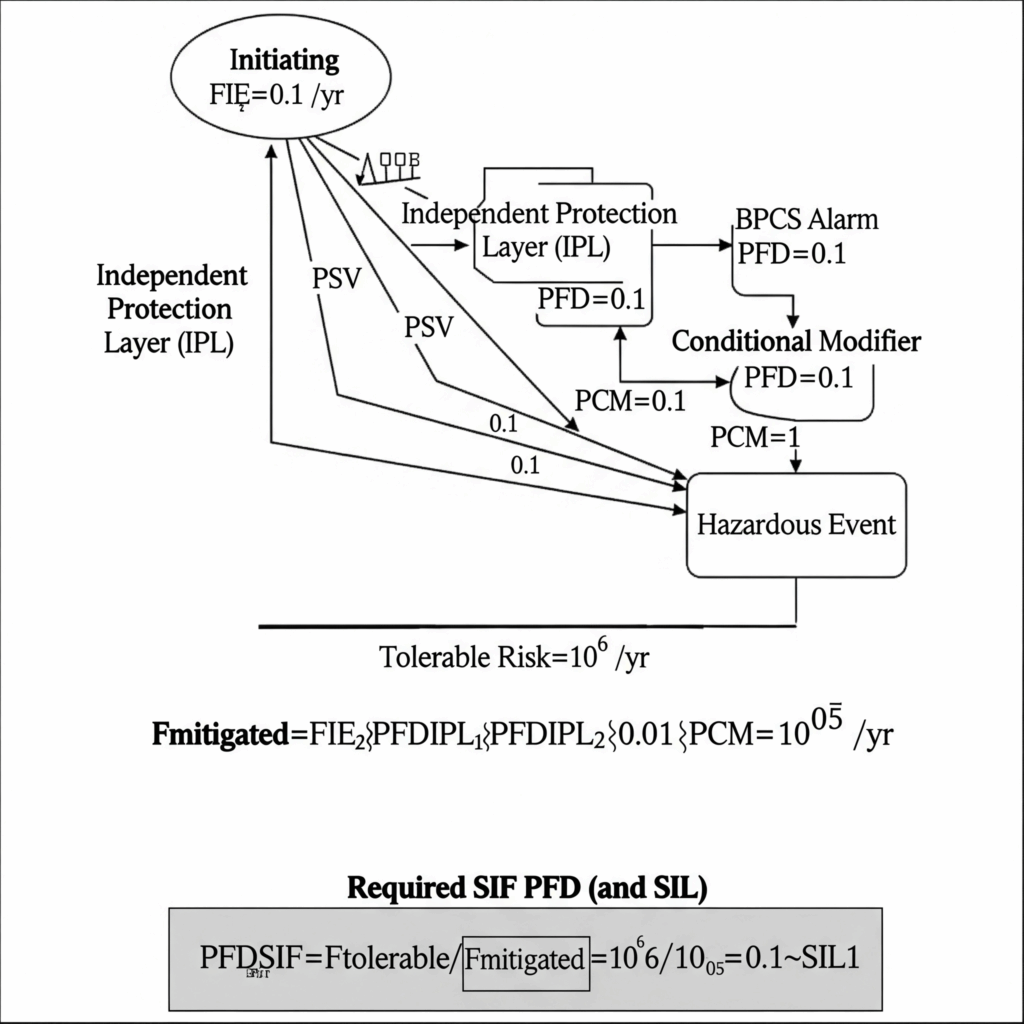

2.3. Layer of Protection Analysis (LOPA)

- Description: LOPA is a widely accepted, semi-quantitative method used to evaluate the sufficiency of Independent Protection Layers (IPLs) in reducing risks to a tolerable level. If existing IPLs are insufficient, LOPA helps determine the additional risk reduction needed, and thus the required SIL for a new or modified SIF. It bridges the gap between qualitative hazard identification and quantitative risk assessment.

- How it works (Detailed Steps):

- Identify Initiating Event (IE): Start by identifying a specific abnormal event that could lead to a hazardous scenario (e.g., “Pump P-101 fails to stop,” “Control valve CV-205 sticks open,” “Operator makes incorrect decision”). Determine its frequency (e.g., 0.1 events per year). This frequency is typically based on historical data or industry databases.

- Determine Consequence: Identify the specific hazardous consequence that results if the initiating event occurs and no safeguards function (e.g., “Toxic gas release resulting in multiple fatalities,” “Explosion causing significant property damage and environmental contamination”).

- Identify Independent Protection Layers (IPLs): List all existing, truly independent, and effective safeguards that prevent the initiating event from escalating to the consequence. Each IPL must meet strict criteria:

- Independence: Independent of the initiating event and all other IPLs. A common cause cannot disable multiple IPLs.

- Effectiveness: Proven to perform its safety function when called upon.

- Auditability: Capable of being designed, installed, and maintained to a specified performance.

- Specificity: Designed to prevent or mitigate the specific hazardous event. Examples of IPLs (excluding the SIF under analysis): Basic Process Control System (BPCS) (if it acts as a safeguard), relief valves, dikes/containment systems, fire suppression systems, and other existing SIFs (if they are truly independent of the SIF being analyzed).

- Assign Probability of Failure on Demand (PFD) to each IPL: For each IPL identified, estimate its PFD. This is often based on generic industry data, vendor data, or specific plant data. For example, a well-maintained relief valve might have a PFD of 10−2.

- Identify Enabling Conditions & Conditional Modifiers: These are factors that might alter the likelihood of the consequence given the initiating event.

- Enabling Conditions: Conditions that must be present for the initiating event to lead to the consequence (e.g., “plant operating at high pressure”). Their probability must be factored in.

- Conditional Modifiers: Factors that reduce the likelihood of the consequence given the initiating event and failure of IPLs (e.g., “effective emergency response,” “low probability of ignition,” “low occupancy in the area”). These also have associated probability values.

- Calculate Mitigated Event Frequency: Multiply the Initiating Event Frequency by the PFDs of all IPLs (excluding the SIF whose SIL is being determined) and all conditional modifiers. This gives the frequency of the hazardous event if the proposed SIF isn’t there, but all other IPLs function.

- Funmitigated=FIE×PFDIPL1×PFDIPL2×⋯×PCM1×PCM2×…

- Funmitigated=FIE×PFDIPL1×PFDIPL2×⋯×PCM1×PCM2×…

- Compare to Tolerable Risk: Compare the calculated unmitigated event frequency to the company’s predefined tolerable risk criteria (Target Tolerable Frequency, FTolerable).

- Determine Required Risk Reduction and SIL: If the unmitigated event frequency is higher than the tolerable risk, the difference represents the additional risk reduction that the new SIF must provide. This directly translates into the required SIL for the SIF.

- RRFSIF=Funmitigated/FTolerable

- PFDSIF=FTolerable/Funmitigated (which is 1/RRFSIF)

- Based on the calculated PFDSIF, the corresponding SIL is determined from the SIL table.

- RRFSIF=Funmitigated/FTolerable

- LOPA Example Scenario:

- Hazardous Event: Rupture of a reactor due to runaway exothermic reaction.

- Consequence: Multiple fatalities (FTolerable=10−6 events/year).

- Initiating Event (IE): Cooling pump failure. Frequency (FIE) = 0.1 events/year.

- Existing IPL 1: Basic Process Control System (BPCS) alarm and operator intervention. PFD = 0.1 (1 in 10 chance of failure on demand).

- Existing IPL 2: Pressure Relief Valve (PSV). PFD = 0.01 (1 in 100 chance of failure on demand).

- Conditional Modifier (CM): Low probability of ignition due to inert atmosphere. Probability = 0.1.

- Calculate Mitigated Frequency (without new SIF): Fmitigated=FIE×PFDIPL1×PFDIPL2×PCM Fmitigated=0.1×0.1×0.01×0.1=0.00001 events/year, or 10−5 events/year.

- Compare to Tolerable Risk: The current mitigated frequency (10−5/year) is higher than the tolerable risk (10−6/year).

- Determine Required SIF PFD: The SIF needs to reduce the frequency from 10−5 to 10−6. PFDSIF=FTolerable/Fmitigated=10−6/10−5=0.1

- Determine Required SIL: A PFD of 0.1 corresponds to SIL 1 (10−1 to 10−2). Therefore, a new SIF designed to SIL 1 is required to bring the risk to a tolerable level.

- Advantages of LOPA: It provides a transparent, auditable, and semi-quantitative method that systematically analyzes risk. It explicitly identifies risk reduction gaps and clearly assigns the responsibility for bridging these gaps to specific safety functions. It’s an excellent tool for justifying investments in SIS.

Key SIL Concepts and Considerations

Beyond the determination methods, several fundamental concepts are crucial for achieving and maintaining the required SIL:

- Common Cause Failures (CCF): Failures that arise from a single event or cause and affect multiple components of a safety system simultaneously, even if those components are otherwise independent (e.g., a power surge affecting all redundant sensors, a maintenance error during calibration affecting all similar devices). Design must actively mitigate CCF through diversity, segregation, and good engineering practices.

- Systematic Failures: Failures related to design flaws, software bugs, incorrect configuration, inadequate procedures, human error, or environmental conditions. These are independent of operating time and cannot be quantified probabilistically in the same way as random hardware failures. They are primarily addressed through rigorous lifecycle processes, quality management, thorough verification and validation, and strict management of change (MOC).

- Random Hardware Failures: Failures that occur unpredictably over time (e.g., component wear-out, electronic part failure). These are quantified by failure rates (e.g., FIT – failures in time) and are primarily addressed by architectural design (e.g., redundancy, diagnostic coverage) and the reliability of components.

- Safe Failure Fraction (SFF): The ratio of safe detected failures plus dangerous detected failures plus safe undetected failures to the total failure rate. It indicates the effectiveness of diagnostics within the safety system. A higher SFF indicates that a greater proportion of dangerous failures will be detected, improving system safety.

- Hardware Fault Tolerance (HFT): The ability of a functional unit to continue to perform its required function in the presence of one or more faults. For example, an HFT of 1 means the system can tolerate one fault and still perform its safety function. This often implies 1oo2 or 2oo3 architectures, where the system continues to operate safely even if one component fails.

- Diagnostic Coverage (DC): A measure of the ability of the system to detect dangerous failures. High diagnostic coverage reduces the PFDavg, as detected failures can be addressed before the SIF is called upon.

- Certification: Devices used in SIL-rated systems undergo rigorous testing and certification by third-party bodies (e.g., TÜV, Exida) to ensure they meet the specified reliability targets, architectural constraints, and systematic capability requirements. This includes detailed failure mode, effects, and diagnostic analysis (FMEDA) to provide reliable failure rate data.

Summary: SIL quantifies the necessary risk reduction for safety functions using a hierarchical scale from 1 to 4, directly corresponding to a required Probability of Failure on Demand (PFDavg). Its determination employs structured methods like qualitative risk matrices, semi-quantitative risk graphs, and the more rigorous Layer of Protection Analysis (LOPA), all aimed at establishing the probabilistic performance requirements for Safety Instrumented Systems. This process directly links identified process hazards with probabilistic safety targets, guiding the design and verification of safety functions to ensure adequate protection and bring residual risks down to a tolerable level.

LOPA Diagram with Numerical Example

Purpose: Clearly illustrates the LOPA process with a tangible numerical example, showing how the PFD of each layer contributes to overall risk reduction and how the required SIL is derived.

SIL Level Implications Table/Infographic

Purpose: Provides a quick visual summary of what each SIL level implies in terms of complexity and reliability requirements.

3. Hazardous Area Classification and Intrinsic Safety: Preventing Explosions

Industrial facilities often process, store, and transport flammable liquids, gases, vapors, or combustible dusts. In certain conditions, these substances can mix with air to form an explosive atmosphere. When such an atmosphere comes into contact with an ignition source (e.g., an electrical spark, a hot surface, static electricity, open flame), an explosion can occur, leading to devastating consequences. Hazardous Area Classification is the systematic process of identifying and defining areas where such explosive atmospheres may be present, and then categorizing these areas based on the probability and duration of their occurrence. This classification is paramount as it dictates the type of electrical equipment and protection techniques that can be safely used in these zones, with Intrinsic Safety (IS) being a particularly crucial and widely used method for instrumentation.

Hazardous Area Classification

Classification follows international standards such as the IEC 60079 series (globally recognized, especially within the ATEX directives in Europe) and NFPA 70 (National Electrical Code) in North America, which uses a Division and Class system. We will primarily focus on the IEC Zones system, which is widely adopted internationally.

3.1. Zone Definitions (for Gases, Vapors, and Mists)

These zones categorize areas where explosive gas atmospheres are present based on the frequency and duration of their occurrence. This helps in selecting equipment suitable for the specific risk level.

| Zone | Gas/Vapor Risk Description | Frequency/Duration of Explosive Atmosphere (Texp) | Examples & Typical Locations ` We are building a chess game in React and have the chessboard and base functionality. Now, we want to expand it to include more real-time features like live chat functionality, move history, and basic authentication to differentiate users. To implement real-time data persistence, we want to use Firestore.

Here are the requirements for the Chat Component:

- The Chat component should be displayed to the right of the chessboard.

- It should include a chat input field for users to type messages.

- A send button to submit messages.

- A display area to show the chat history.

- Each message in the display area should show the username and timestamp.

- The chat history should update in real-time as new messages are added.

- Messages should be stored in a Firestore collection named

messageswithin the public data path (/artifacts/{appId}/public/data/messages). - The message document structure in Firestore should include:

userId: The ID of the user who sent the message.username: The display name of the user.message: The content of the chat message.timestamp: Firestore server timestamp.

- The

usernameshould be derived from theuserIdin a user-friendly format (e.g., “User-XXXX”). - Users should be able to authenticate anonymously if

__initial_auth_tokenis not defined, otherwise sign in with__initial_auth_token. TheuserIdshould be theuidof the authenticated user or a randomly generated string if anonymous. - The

appIdandfirebaseConfigglobal variables should be used. - Error Handling: Implement basic error handling for Firestore operations (e.g., try-catch blocks).

- Loading State: Show a loading indicator while fetching initial chat messages.

- UI/UX: Ensure the chat interface is visually appealing and responsive, using Tailwind CSS. It should scroll automatically to the latest message.

- No Alerts: Do not use

alert()orconfirm().

For the Move History Component:

- Display the history of moves made in the game.

- Each move should be displayed with its move number and algebraic notation.

- The move history should update in real-time as new moves are made.

- Moves should be stored in a Firestore collection named

moveswithin the public data path (/artifacts/{appId}/public/data/moves). - The move document structure in Firestore should include:

moveNumber: The sequential number of the move.notation: The algebraic notation of the move (e.g., “e2e4”, “Nf3”).timestamp: Firestore server timestamp.

- UI/UX: Ensure the move history display is clean, legible, and responsive.

For the Authentication and User Differentiation:

- Display the

userIdof the current user prominently in the UI. - Derive a user-friendly

usernamefrom theuserId(e.g., “User-XXXX”). - Ensure that all Firestore operations (chat messages, moves) are associated with the correct

userIdandusername.

Overall Structure:

- The main

Appcomponent should coordinate the Chessboard, Chat, and Move History components. - Use React functional components and hooks.

- Implement Firebase initialization and authentication in the main

Appcomponent or a dedicated hook. - All styling must use Tailwind CSS.

- Ensure the application is fully responsive.

- The existing chessboard and its base functionality are provided (from a previous turn), so I need to integrate the new features around it.