Blog

Process Control Systems

Comprehensive Overview of Process Control Systems

Process control systems refer to the methodologies and technologies employed across industries to regulate production processes, ensuring output consistency, quality, and operational efficiency. From manufacturing plants and chemical processes to power generation and pharmaceutical production, process control systems are integral in maintaining stability and reliability of numerous industrial applications. Effective process control can significantly reduce waste, enhance safety, optimise energy usage, and improve the overall profitability and sustainability of operations.

Overview of Process Control

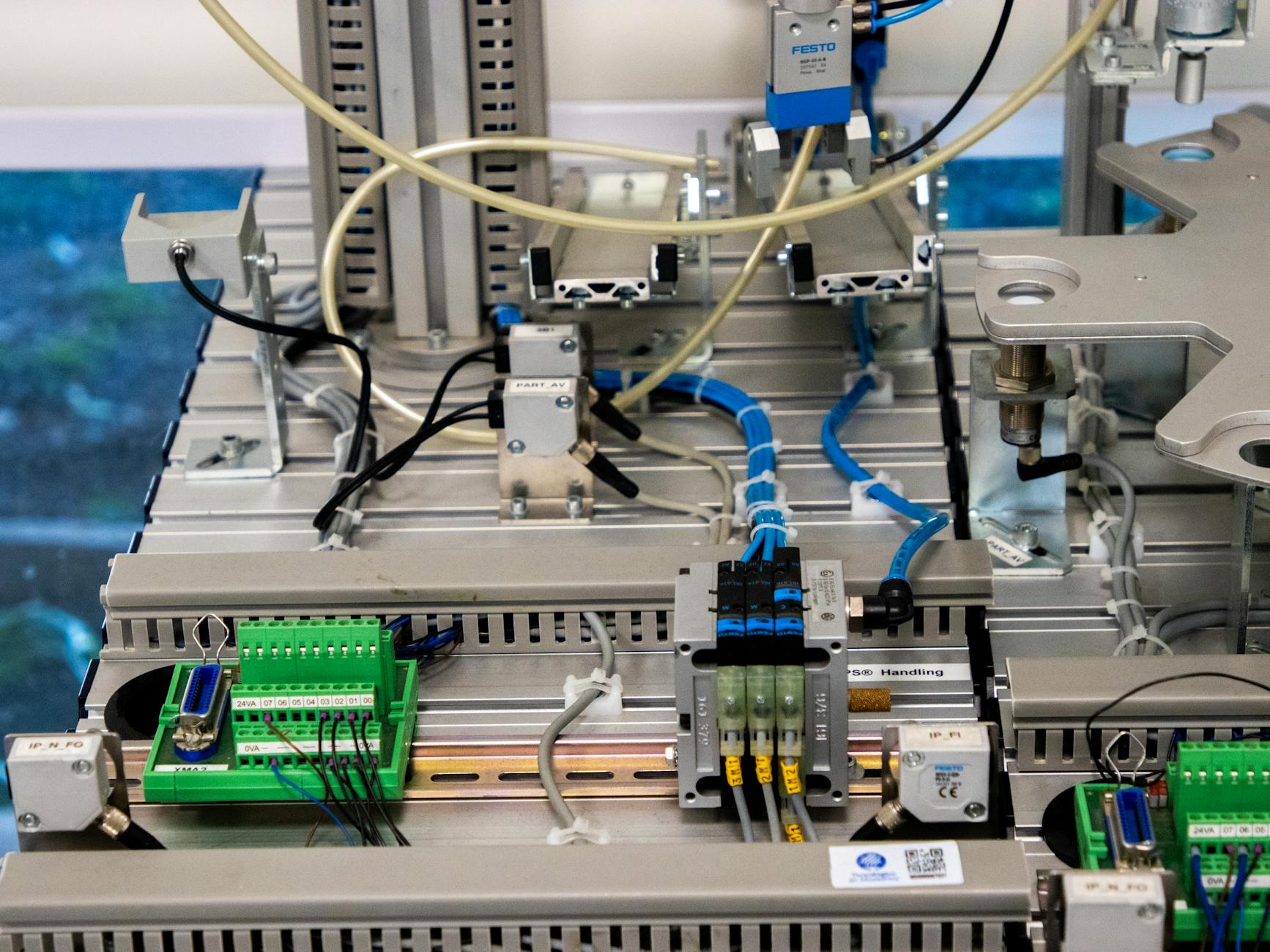

At its core, process control systems involve measurement, comparison, calculation, and corrective action, which function collaboratively to maintain the desired level or output of any given process. Sensors measure specific parameters (such as temperature, pressure, or concentration), whereas controllers analyse data and determine necessary adjustments. Lastly, actuators carry out the commands issued by controllers, adjusting the parameters to meet desired conditions. The primary objective of these controls is ensuring operational consistency, efficiency, safety, and economics in various industrial processes.

The stages of process control typically include:

- Measurement: Sensors and instruments accurately evaluate current conditions within the process.

- Comparison: Controllers evaluate these measured values against predefined set points or intended reference values.

- Calculation: Controllers compute the required corrective action using control algorithms based on differences between measured values and desired outcomes.

- Action: Actuators or control elements make necessary adjustments to the process.

Understanding this overview helps organisations adopt effective process control systems and optimise their industrial operations for superior operational reliability and productivity.

Types of Control Systems

Control systems are broadly categorised into two primary types, each defined by how they interact with system outputs:

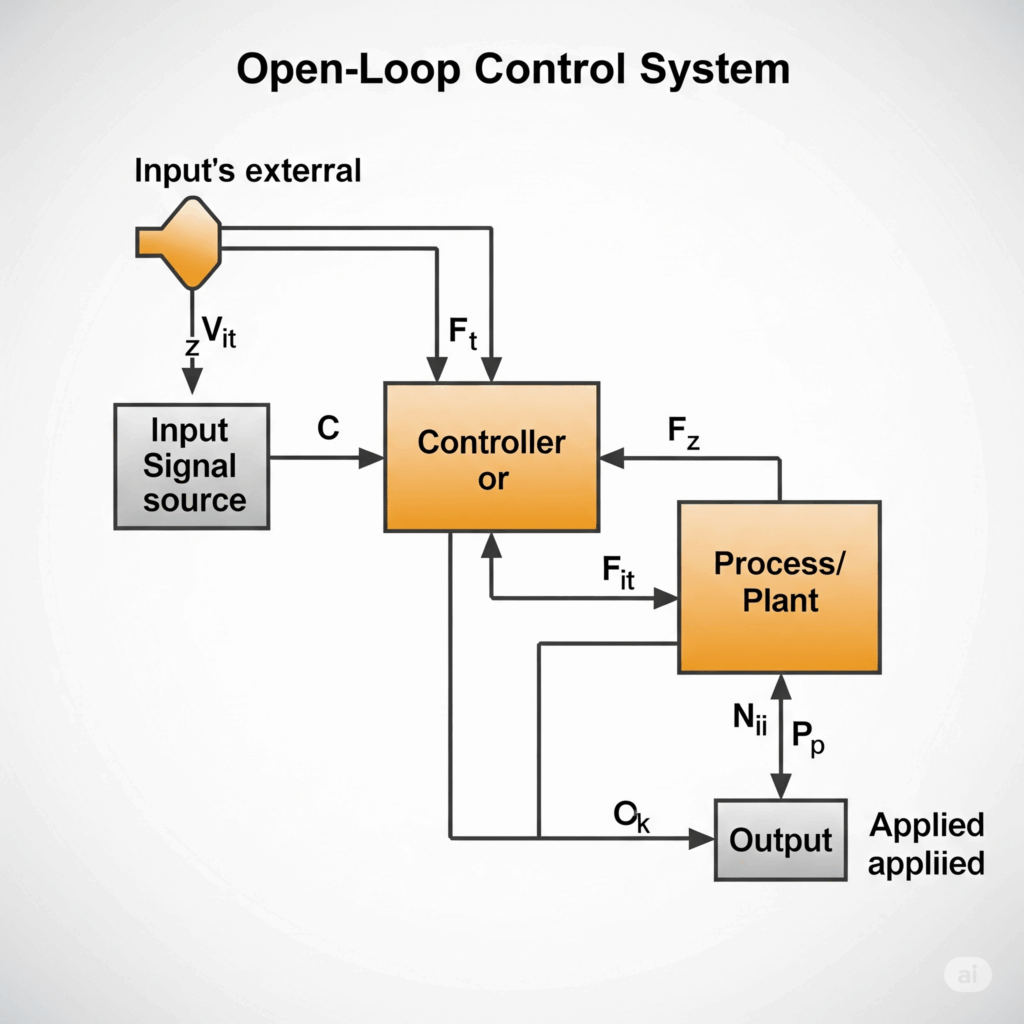

1. Open-Loop Control Systems

An open-loop control system, also known as a non-feedback system, acts without considering output feedback. That means output variations do not impact system performance. The controller delivers signals to actuators without checking and adjusting continual output measures, making this type simpler in structure but less adaptable to changes and disturbances.

Key features:

- Simplicity in design and construction

- Low maintenance requirements due to lack of feedback sensors

- Economical initial investment

- Inexact and potentially unstable under varying conditions

- Commonly used in systems where accuracy is not critical

Examples include: Washing machines, toasters, or a basic heating system that maintains a fixed temperature without sensing changes.

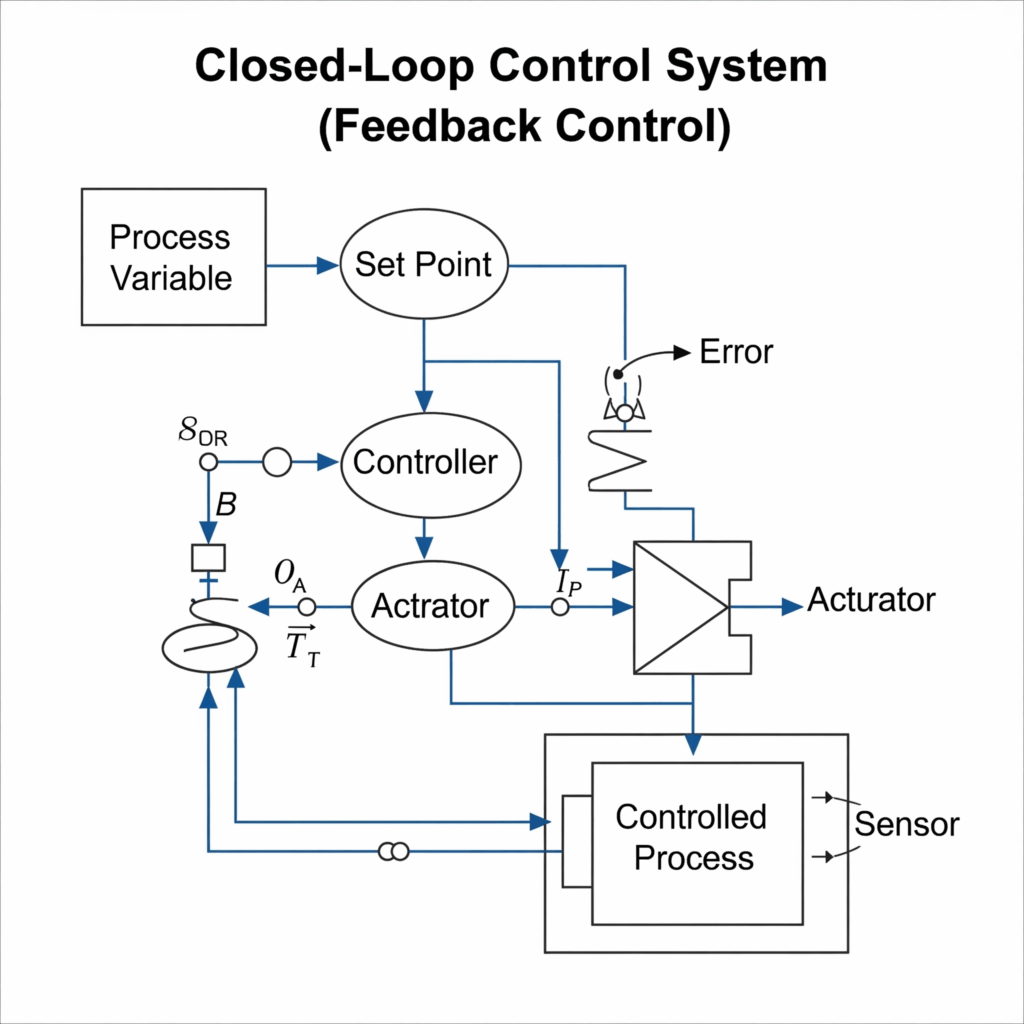

2. Closed-Loop Control Systems (Feedback Control)

Closed-loop control systems differ from open-loop systems as they integrate continuous feedback from system outputs into their operation. The sensors measure the controlled variables, sending this data back to the controller, which then takes corrective actions if deviations from the predefined set point are present. Owing to feedback measurements, these systems can promptly adjust to external disturbances and maintain an accurate, stable output.

Key features:

- Precise control and stable operation

- Continuous monitoring and immediate corrective actions

- Adaptive and responsive to external or internal disturbances

- Generally, more expensive and complex to implement and maintain

- Widely used in critical industrial processes, ensuring performance accuracy

Examples include: Air conditioning systems, automatic pilot systems in aircraft, and thermostatic control systems in reactors.

Control Theory: Understanding PID Controllers

Among various methodologies belonging to control theory, the PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controller stands out as one of the most widely utilised control algorithms due to its simplicity and effectiveness in numerous applications. A PID controller blends three distinct control actions to produce a corrective action:

1. Proportional Control (P)

The proportional control action is directly proportional to the error signal. It instantly responds to the discrepancy between measured output and desired set point, effectively decreasing error magnitude but typically never reaching a zero-error condition by itself.

2. Integral Control (I)

The integral control factor deals primarily with system steady-state errors by summing errors over time. This cumulative error counteracts any persisting discrepancies, driving the system output accurately to equal the set input, thus mitigating control offsets.

3. Derivative Control (D)

Derivative control anticipates the system behaviour by overseeing the rate of change of the error. It helps in predicting and mitigating future errors before they occur, significantly improving the system’s reaction speed and stability.

Key advantages of PID controllers:

- Simple design and easy implementation

- High versatility across different types of industries and applications

- Proven reliability and robustness

- Ability to fine-tune parameters for optimal performance

PID applications: temperature controls in industrial ovens, level control in storage tanks, robotic motion control, automotive cruise-control systems, and numerous other manufacturing processes.

Feedback and Feedforward Control: Complementary Approaches

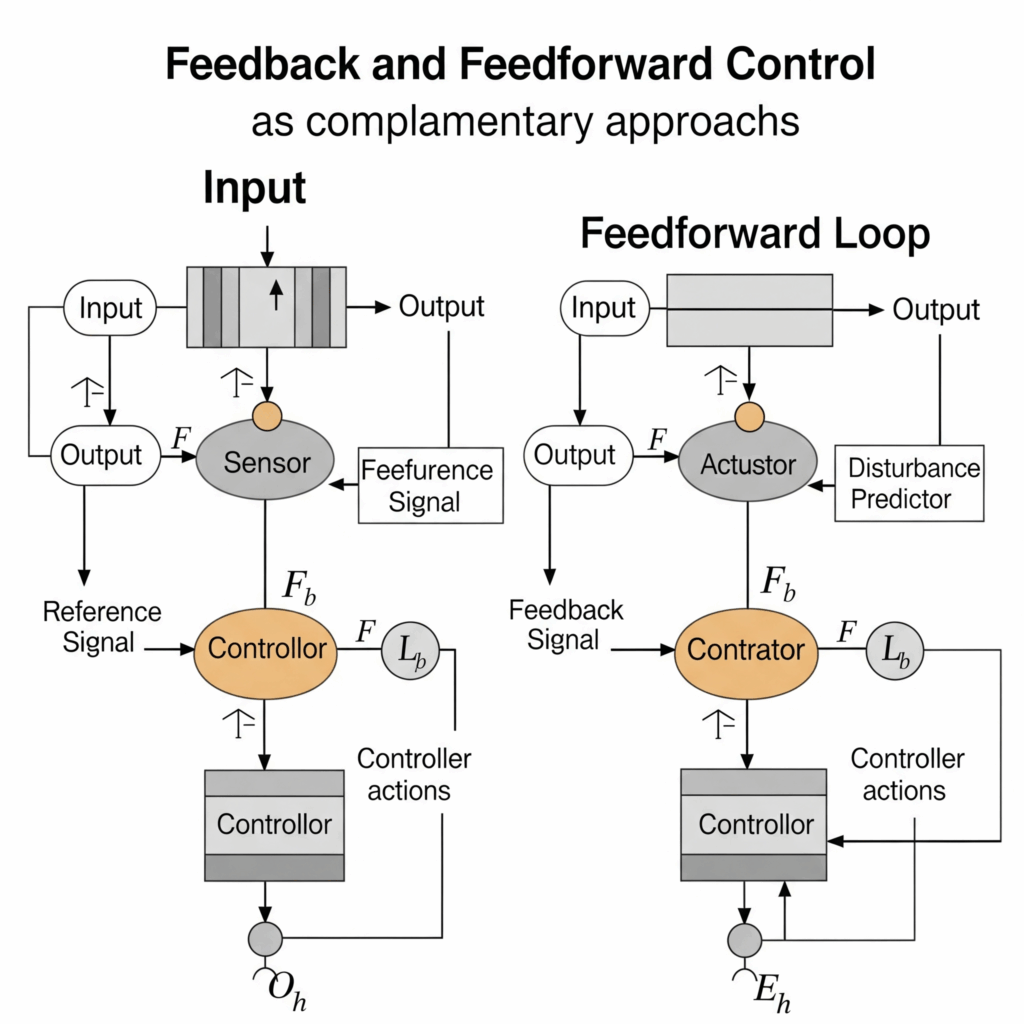

In process controls, feedback and feedforward mechanisms are two essential methods applied to achieve the desired system behaviour:

Feedback Control

As previously mentioned under closed-loop systems, feedback control continuously monitors the process outputs and compares them with the set point. Variances trigger immediate corrective actions, aiming to minimise future errors.

Strengths:

- Accuracy and precision in maintaining set parameters

- Highly effective in dynamic environments with unknown disturbances

Limitations:

- Reactive approach—only responds after deviation has occurred, which may introduce delay

- Potential for oscillations and instability if improperly tuned

Feedforward Control

Feedforward control operates proactively, responding before the disturbance actually affects the process. Through predictive assessments of disturbances or known fluctuations, the feedforward controller anticipates changes and makes pre-emptive corrections. It significantly enhances efficiency by mitigating disturbances prior to their occurrence, minimising process variability.

Strengths:

- Proactive adjustment—minimizes deviations before they impact process outputs

- Reduced reaction time and enhanced stability

Limitations:

- Limited applicability—effective only with known and measurable disturbances

- Dependence on accurate models of disturbances and process characteristics

Combined Use: For optimal performance, many industrial operations integrate both feedforward and feedback strategies simultaneously—feedforward provides anticipatory adjustments, while feedback corrections help refine and stabilise outcomes. This comprehensive approach delivers superior performance and enhances overall operational efficiency.

Conclusion

Process control systems—via open-loop and feedback mechanisms, sophisticated control theories such as PID controllers, and feedforward/feedback strategies—constitute essential components in contemporary industries. Understanding these control strategies and their integration ensures industrial operations achieve exceptional accuracy, efficiency, economic benefit, and safety in modern manufacturing processes.