Blog

Exposure to microplastic makes animals want to eat it more

The insidious spread of microplastics throughout the environment has emerged as one of the most pressing ecological crises of our time. These tiny fragments, less than 5 millimeters in size, are found everywhere – from the deepest ocean trenches to remote mountain peaks, and alarmingly, within the bodies of countless living organisms. While the immediate physical harm caused by larger plastic debris (like entanglement or gut blockage) is well-documented, a more subtle and disturbing consequence of microplastic pollution is coming to light: evidence suggests that exposure to microplastics may actually make animals want to eat them more.

This counterintuitive phenomenon, which researchers are actively investigating, points to complex biological and behavioral alterations in affected species. It raises profound concerns about the long-term impact on ecosystems, food chains, and ultimately, human health.

The Ubiquitous Threat: How Microplastics Enter Animals

Before delving into the “desire to consume,” it’s crucial to understand how pervasive microplastic exposure truly is. Microplastics originate from the breakdown of larger plastic items, the shedding of synthetic fibers from clothing, the wear and tear of tires, and even microbeads in personal care products. They enter ecosystems through various pathways:

- Ingestion: Animals directly consume microplastics present in water, soil, or even their food sources. Filter feeders like mussels and oysters are particularly vulnerable, accumulating large quantities as they process water for nutrients.

- Inhalation: Airborne microplastics can be inhaled by terrestrial animals, with particles potentially reaching respiratory systems and even the bloodstream.

- Dermal Contact: While less studied, direct contact with plastic-laden environments could also lead to absorption, especially for smaller particles.

- Trophic Transfer: A critical pathway is the “trophic transfer” or biomagnification. When smaller organisms that have ingested microplastics are consumed by larger predators, the plastic (and any associated toxins) moves up the food chain, accumulating in higher concentrations in apex predators.

Beyond Accidental Ingestion: The Alluring Trap

Initially, the prevailing understanding was that animals ingested microplastics accidentally, mistaking them for food due to their small size, color, or shape. A sea turtle might mistake a plastic bag for a jellyfish, or a bird might confuse brightly colored plastic pellets (nurdles) for fish eggs. While this accidental ingestion remains a significant problem, recent research suggests a more sinister mechanism at play: exposure itself might alter an animal’s perception and behavior, leading them to actively seek out and consume more microplastics.

Several hypotheses are being explored to explain this alarming phenomenon:

- Biofilm Formation and Chemical Lures: When plastics enter aquatic or terrestrial environments, their surfaces quickly become colonized by a diverse array of microorganisms, forming what is known as a “biofilm.” This biofilm, comprising bacteria, algae, and other microbes, can emit chemical cues that are naturally attractive to certain animals, signaling the presence of food. For instance, some studies have found that plastics colonized by algae can emit dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a sulfur compound that is a natural foraging cue for seabirds like albatrosses. Thus, the plastic, once an inert object, transforms into a seemingly appealing food source. This “olfactory trap” tricks animals into actively seeking out and consuming microplastics that are, in reality, devoid of nutritional value and potentially harmful.

- Nutritional Deficiencies and False Satiation: Chronic exposure to microplastics can lead to a false sense of satiation. Animals, particularly those with small stomachs or digestive tracts, may ingest microplastics that fill their gut but offer no nutritional content. This can lead to a feeling of fullness without actual nutrient absorption, driving the animal to continue foraging. If real food is scarce or difficult to obtain, and plastic is abundant, the animal might repeatedly ingest microplastics in a futile attempt to satisfy its nutritional needs. This creates a vicious cycle of malnutrition and continued plastic ingestion.

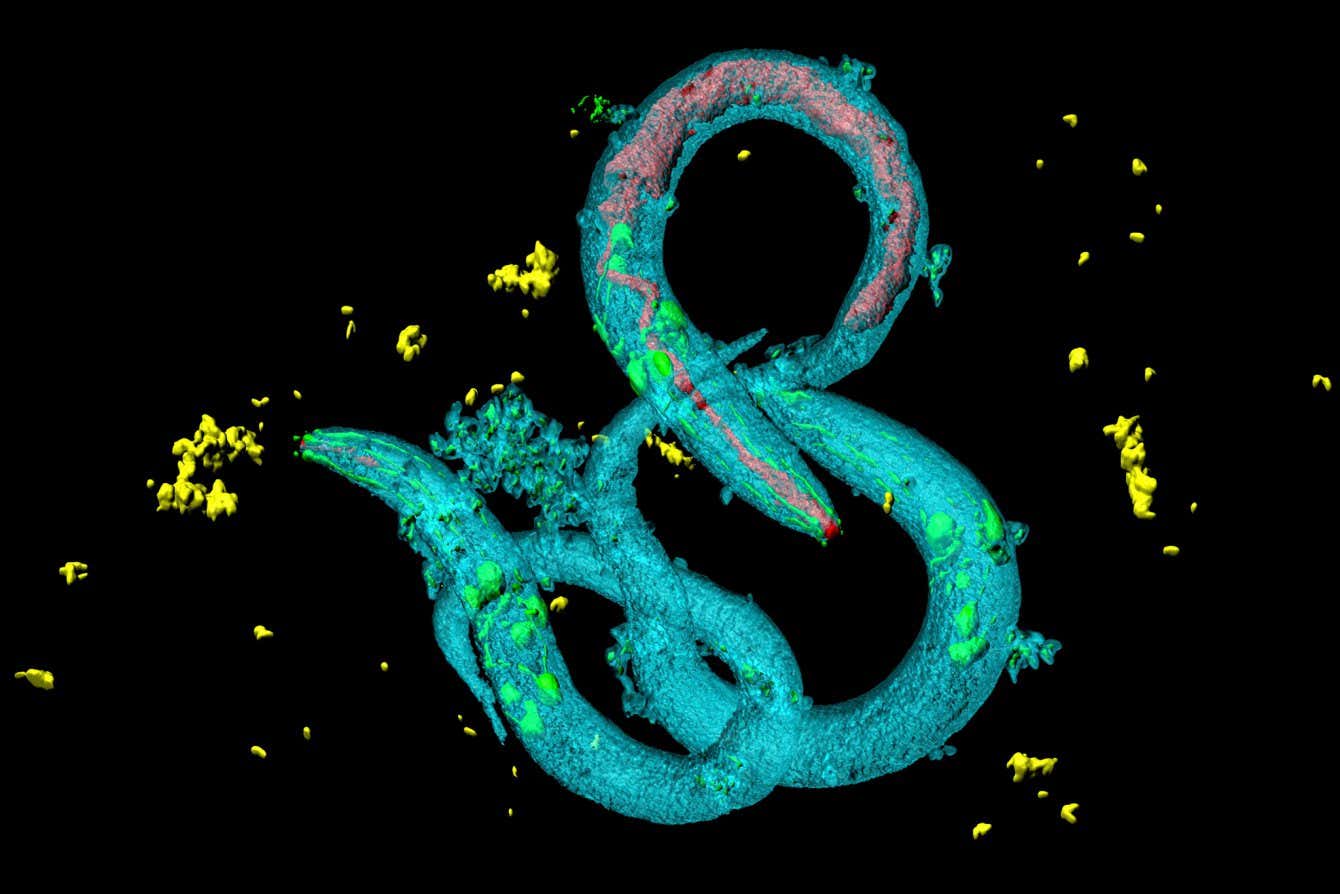

- Disruption of Metabolic and Neurological Pathways: The impact of microplastics goes beyond physical blockage. Once ingested, microplastics can leach chemicals (additives from manufacturing, or pollutants adsorbed from the environment) into the animal’s tissues. These chemicals, many of which are endocrine disruptors, can interfere with normal physiological processes, including metabolism, appetite regulation, and neurological function. Studies on rodents, for example, have shown that microplastics can cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the brain, leading to cognitive decline and potentially altering behaviors related to feeding. If these chemicals disrupt the delicate balance of hormones and neurotransmitters that control hunger and satiety, animals might experience altered feeding patterns, potentially increasing their desire or compulsion to consume more non-food items, including plastics.

- Physical Damage and Inflammation: The physical presence of microplastics can cause internal abrasions, inflammation, and damage to the digestive tract. This chronic irritation and inflammation could potentially alter gut microbiota composition, which is known to influence appetite and behavior. While direct links to increased plastic consumption are still being explored, a compromised gut health could indirectly contribute to abnormal feeding behaviors.

Consequences of the Plastic Craving

The implications of animals actively seeking out and consuming more microplastics are dire:

- Malnutrition and Starvation: As animals fill their stomachs with indigestible plastic, they are unable to consume sufficient nutritious food, leading to severe malnutrition, reduced growth, reproductive failure, and ultimately, starvation.

- Toxic Accumulation: Microplastics act as vectors for various environmental toxins, including persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals, which readily bind to their surfaces. When ingested, these toxins can leach into the animal’s body, bioaccumulating in tissues and organs. This can lead to a range of adverse health effects, including endocrine disruption, immune system impairment, reproductive problems, and organ damage (liver, kidney, brain).

- Reduced Reproductive Success: The physiological stress, malnutrition, and toxic effects of microplastics can significantly impair an animal’s ability to reproduce, threatening population stability and biodiversity.

- Disruption of Food Webs: If primary consumers are increasingly ingesting plastic, this contamination propagates up the food chain, impacting larger predators and potentially disrupting entire ecosystems. The notion of biomagnification of plastics and associated toxins is a significant concern for food security.

- Human Health Risks: As humans are at the top of many food chains, the accumulation of microplastics and their associated chemicals in animals consumed by people raises direct concerns for human health. We are inadvertently ingesting microplastics through seafood, meat, and even drinking water, making us part of the very cycle we have created.

The Urgent Need for Action

The emerging understanding that microplastic exposure might lead animals to crave and consume more plastic highlights the complexity and severity of plastic pollution. It’s a problem that extends beyond simple physical harm, delving into behavioral and neurological alterations. Addressing this requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Drastic Reduction in Plastic Production and Consumption: This is the most critical step. Moving towards a circular economy and investing in truly biodegradable alternatives is essential.

- Improved Waste Management and Recycling Infrastructure: Preventing plastic from entering the environment in the first place is paramount.

- Enhanced Research: Continued research is vital to fully understand the mechanisms behind altered feeding behaviors, the long-term health impacts, and potential mitigation strategies.

- Public Awareness and Education: Raising global awareness about the insidious nature of microplastic pollution is crucial to drive individual and systemic change.

The prospect of animals being “addicted” to plastic, even inadvertently, paints a grim picture of a world increasingly shaped by human waste. It underscores the urgent need for comprehensive and immediate action to curb plastic pollution and protect the delicate balance of life on Earth